Localizing Development: Why Haven’t We Made More Progress?

This post is part of a series of articles where we will explore the landscape, challenges, and potential solutions to support localizing development. We will also be exploring bright spots, and creative ways our colleagues are moving development and international relief closer to the communities they impact.

This article and series were developed through consultative conversations with our global team at GDI and cross-sector experts representing diverse perspectives around the world. We reviewed more than 50 articles and opinion pieces, and over 20 long-form reports. We spoke with 25 individuals at non-profits, networks, foundations, activist organizations, and social businesses, all of whom engage deeply with this topic in their work. We are deeply grateful for their time and insights.

For more context on the language we use in this series, please review this article.

Despite their proximity to crisis-affected communities, deep contextual understanding, and tailored programmatic solutions, domestically-registered NGOs and civil society organizations (CSOs) in low-middle income countries (LMIC) receive disproportionally little funding from global north donors. In our inaugural post on localizing development, we observed that funders are collectively and individually demonstrating a will to change the status quo through public commitments to increase the share of money going to these groups. Yet, less than 6% of bilateral funding and less than a quarter of the philanthropic funding that is going to CSOs goes to domestically registered CSOs.

Helping Identify and Understand Barriers to Progress

We went into these conversations with a desire to surface practical, scaleable, and impactful solutions. A lot has been written and said on this topic, but most pieces fall short of laying out a concrete and comprehensive set of actions that systematically address barriers to progress. Our first goal in this exploration was to understand the full range of barriers so that we could then apply GDI’s comparative advantage to the issue; our ability to conceptualize and stand up initiatives that can bring about systems change, our ability to bring together diverse actors in multi-stakeholder initiatives, and our openness and flexibility to feedback and constructive criticism that ensures initiatives are relevant and impactful.

In this post, we lay out our understanding of the set of barriers holding back donors from giving directly to domestically registered NGOs. Subsequent posts will discuss proposed solutions. We are not the first to attempt this exercise. However, we hope that our insights, synthesized from speaking with a diverse group of actors, will deepen the understanding in the field and create a framework for action.

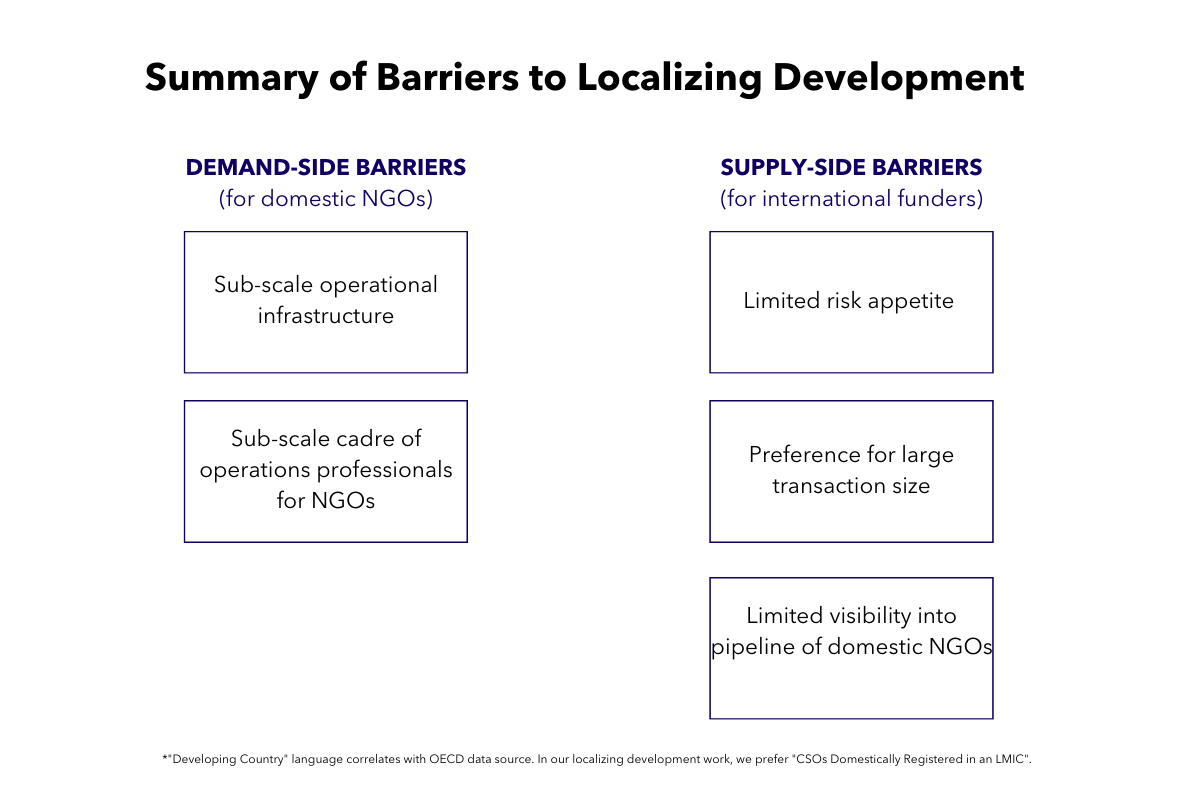

Figure 1: Summary of barriers to localizing development

Demand-Side Barriers: Operational infrastructure and operational talent

Barriers exist on both the demand (organizations looking for funding, in this case, domestically registered NGOs) and supply (organizations providing funding, in this case, global north funders) sides.

On the demand side, the issues are two-fold:

- Domestically-registered NGOs typically have sub-scale operational infrastructure. They often lack the resources to undertake complex financial reporting, audit, and compliance activities. Capacity for grant-writing, monitoring & evaluation activities, dedicated fundraising, and marketing is also limited. This is a critical constraint because global north donors tend to conflate the performance of domestically registered NGOs with their ability to undertake financial compliance and risk management. While this conflation itself is deeply problematic as discussed later, the limited ability of organizations to undertake these functions hold them back from accessing international funding. This resource constraint is itself a manifestation of historical inequities. International NGOs, many of whom emerged post the two World Wars, had a headstart in accessing global north funding, building cash reserves and getting to the scale at which they could create dedicated teams for compliance, finance, grant-writing and M&E. These functions, often centralized in their global north headquarters, give them the platform to rapidly expand to new issue areas and geographies where they compete with and crowd out domestically registered NGOs. Moreover, the international funding that domestically registered NGOs do access are typically earmarked for specific projects. Very little funding is available to cover indirect costs that can be put toward institution building. This limits their ability to hire operational staff and build operational infrastructure (such as IT systems) that are project-agnostic.

- This brings us to the second demand-side challenge: domestically-registered NGOs typically have to work within a sub-scale cadre of operations professionals. Related to the challenges of funding continuity, the pool of skilled operational staff available to domestically registered NGOs is limited. There is no dearth of talented individuals. Limited funding to invest in operations at the organization level, however, when rolled up to the ecosystem, leads to limited jobs and career pathways in non-profit operations. The opportunities that do exist are concentrated in the country offices of international NGOs. Limited career pathways also translate into limited demand for degree or certification programs that cover accounting, financial reporting, and auditing specifically for the nonprofit industry. Additionally, individuals with experience writing grants for donors that often have very exacting and lengthy requirements similarly tend to be absorbed by larger international NGOs. The result is a limited professional cadre of operational talent available to domestic NGOs.

Bridging the Gap between Donors and Domestically Registered NGOs

Many individuals and organizations believe that these barriers are in fact manifestations of the exaggerated risk perceptions of donors. We agree with their assessment. Our divergence comes rather in deciding what to do with this assessment. Some people and organizations in this space believe that the onus of lowering these barriers lie solely with donors – they should lower their threshold for compliance and increase their appetite for risk. This is a fair and ambitious goal. They also, however, view working with domestically registered NGOs to increase their compliance capabilities as further perpetuation of colonial paradigms that impede localization in the first place. We understand and appreciate this perspective.

We also believe that working with both donors and domestically registered NGOs is necessary given that many donors have constituents that require a certain level of oversight. Incremental changes that expand the capacity of the latter to receive international funding, even with the present constraints of donor requirements and perceptions, is a step toward localizing development. We take to heart their concerns around replicating similar power dynamics where a few large domestic NGOs step into the place of international NGOs, not inserting yet another intermediary that “grabs power” and recognizing that just expanding operational capacity for domestic NGOs is not the end goal. These concerns have been critical in shaping our solution to the demand-side barriers, which we will lay out in the next post.

Donor Barriers: Risk appetite, transaction size and limited visibility into the pipeline

Donors face their own set of constraints and challenges that keep them from giving to domestically registered NGOs. These include:

- Limited risk appetite: As many have rightly pointed out, the limited risk appetite of donors lies at the heart of this issue and drives some of the other barriers. Where does this limited risk appetite come from? First, assumptions about risk in localization efforts are not grounded in empirical evidence, but are driven by perception, as the 2021 ODI literature review on localization in humanitarian settings points out. Global North donors perceive domestically registered NGOs to have low capacity and higher vulnerability to pressure and bias given their proximity to local communities, which can drive higher rates of fraud and aid diversion. The ODI literature review finds that studies that have questioned this assumption find both international and domestic organizations to be similarly susceptible to these risks. These perceptions drive stringent compliance requirements and limited trust with domestic NGOs. Second, individuals within global north donor organizations, particularly bilateral organizations, are incentivized to “manage projects cleanly” rather than maximize impact. The risk of funding domestically registered NGOs, and then having an ensuing scandal (no matter how low the probability) far outweighs the reward of the additional impact that the project could create if it were implemented by a domestic NGO. As one of our interviewees put it, “Nobody wants to look bad and everyone wants to look good. But not looking bad is more important.”

- Preference for larger transactions: Many funder organizations themselves are capacity-constrained, with one person managing an outsized grant portfolio, which leads to a preference for fewer, larger transactions. The plan to “staff-up” included in USAID’s recent localization target, for example, is an acknowledgment that funders need to solve for this capacity constraint to give meaningfully to domestic organizations. On the other hand, few domestically registered NGOs have the capacity to absorb large grants. This disconnect is a key barrier that stops funding from flowing to them.

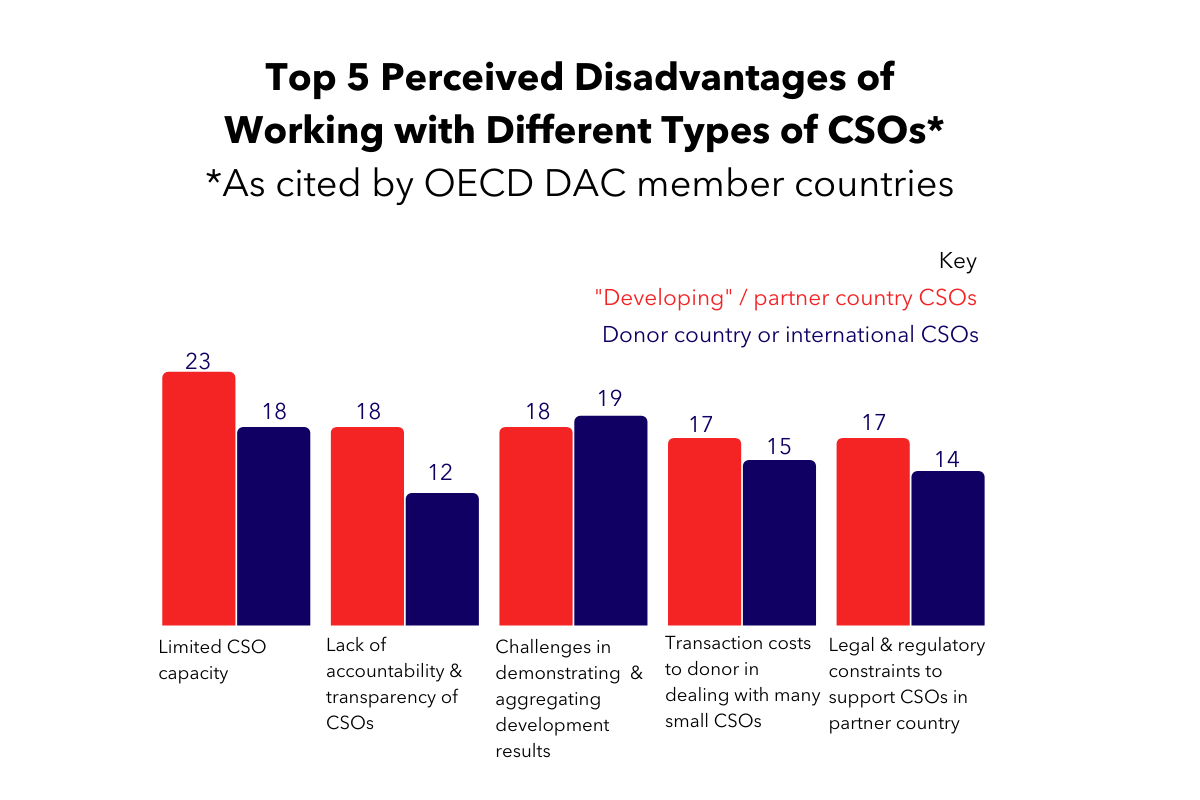

Figure 2: Top 5 perceived disadvantages of working with different types of CSOs as cited by OECD DAC member countries

- Limited visibility into the pipeline of domestic NGOs: Lastly, funders often say that they simply don’t know whom to fund. Even in contexts where there is a fairly robust civil society that receives diverse sources of funding, such as India or South Africa, international funding tends to be concentrated in a few domestic “darlings”. For example, 88% of USAID’s assistance funding to local partners in South Africa went to five organizations. The cadre beneath those large domestic NGOs remains under-supported. The issue is not that they don’t exist – they do. It is rather that they remain invisible to donors in the global north for a multitude of reasons, including limited LMIC presence of donors, and stringent internal strategy documentation processes.

Future Looks Bright

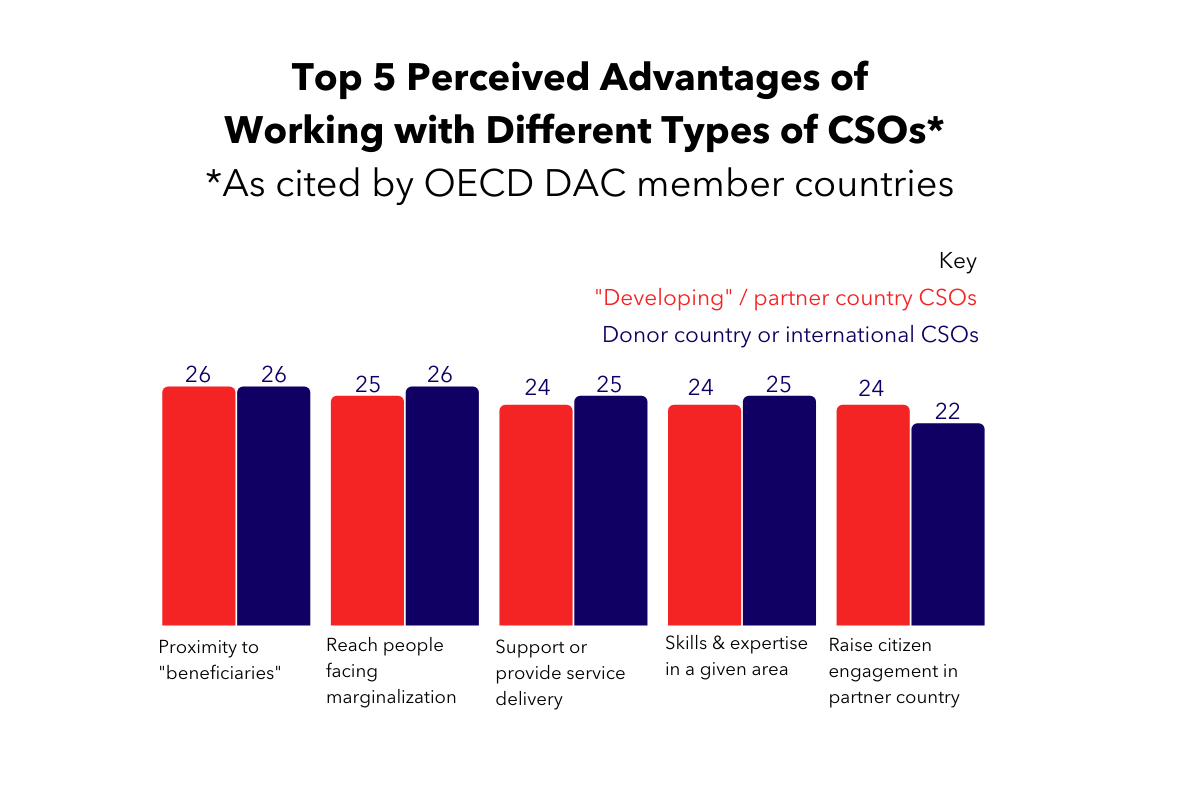

The good news is that funders do not doubt the ability of domestically registered NGOs to deliver excellent programing and impact. A survey undertaken by OECD of Development Assistance Committee (DAC) member countries found that DAC members found similar advantages to working with domestically registered as they did in working with international or donor country NGOs. Yet, despite similar advantages, a disproportionate amount of funding goes to the latter because of barriers discussed above.

Figure 3: Top 5 perceived advantages of working with different types of CSOs as cited by OECD DAC member countries

Donors have also demonstrated the will to change, with multiple public commitments to localize giving. We understand that not every project will benefit from localization. Considerations on input, output, comparative advantage, scale, and speed will make some activities better suited for it than others. (This thought leadership is an excellent framework to help funders nuance their localization strategies). But the current levels of localization are deeply inadequate and unjust, and we have a long way to go. Thoughtful, consistent and innovative initiatives driven by a multitude of actors to localize development make us optimistic that change is possible.

In the next post, we will propose a portfolio of solutions that can begin to dismantle these barriers. As always, we thank you for joining us in our journey to support the decolonizing and localizing development community. We invite any feedback, comments, questions or discussions so that we may continue to grow and evolve from your experiences and expertise. We look forward to partnering with you as we move ahead.

Join our mailing list for updates and follow this series for our latest thinking on GDI’s work in this area.