Localizing Development: Too Little Progress, Too Slowly

This post is the first in a series of articles where we will explore the landscape, challenges, and potential solutions to support localizing development. We will also be exploring bright spots, and creative ways our colleagues are moving development and international relief closer to the communities they impact.

This article and series were developed through consultative conversations with our global team at GDI and cross-sector experts representing diverse perspectives around the world. We reviewed more than 50 articles and opinion pieces, and over 20 long-form reports. We spoke with 25 individuals at non-profits, networks, foundations, activist organizations, and social businesses, all of whom engage deeply with this topic in their work. We are deeply grateful for their time and insights.

For more context on the language we use in this series, please review this article.

Localizing development, or shifting the power to global south organizations, has been discussed as a priority in international development and humanitarian relief for decades. Over the past year, articles and reports on localizing development that call for more equitable power structures within these sectors have proliferated. Yet, this introspection and thought leadership has yet to translate into measurable change in funding flows.

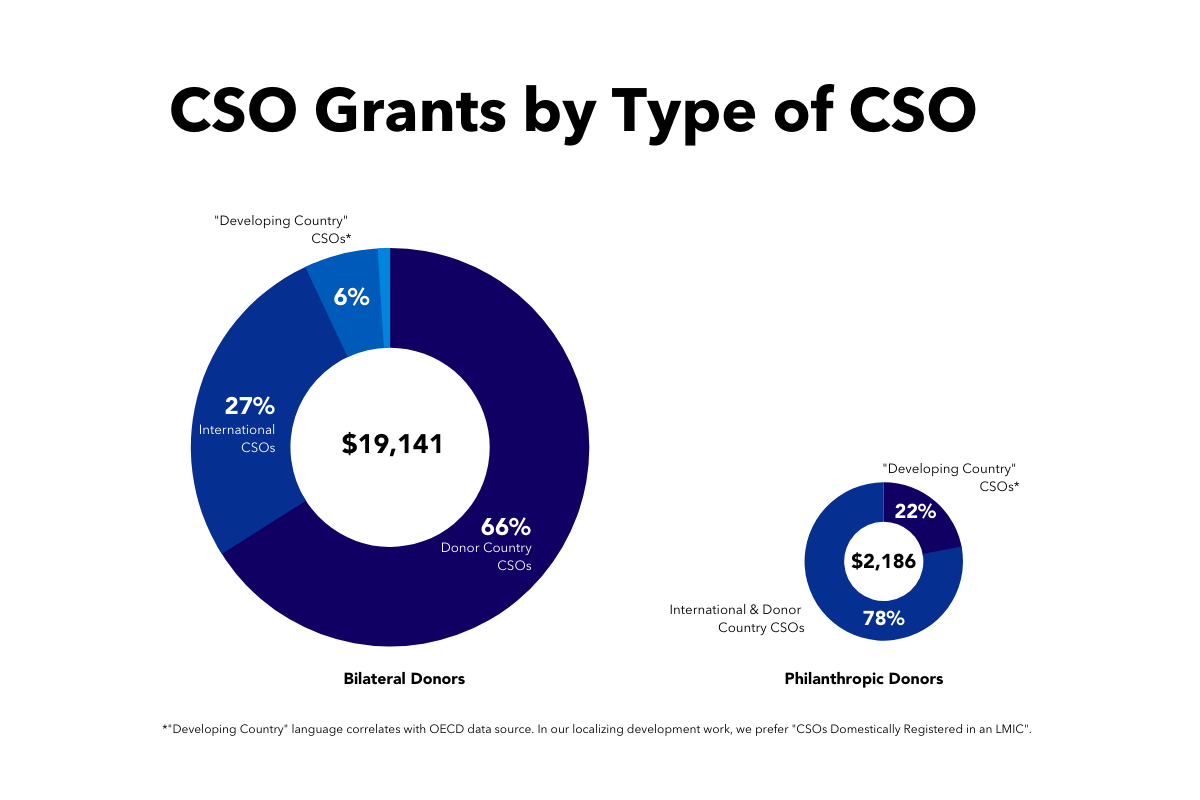

Current State: Only 6% of bilateral funding to NGOs goes to domestically registered NGOs*

Development funding continues to be predominately routed through organizations based in the global north. OECD data shows that of the bilateral overseas development assistance (ODA) provided to non-profits and civil-society organizations, only 6% goes to “developing country CSOs” or domestically registered NGOs. When looking at the share that domestically registered NGOs receive as a share of total bilateral ODA, this number stands at less than 1%.

Source: OECD Data accessed here. See note on methodology at the end of the article.

The story is similar in private philanthropy. Aggregating data from 27 foundations (for which OECD had complete data), we find that less than a quarter of their giving to non-profits goes to domestic NGOs. When considering the share going to domestic NGOs as a share of their total portfolio–which includes giving to research institutions, multilateral organizations, etc.–this share is even lower at ~7%.

Other sources peg the share of funding going to domestic NGOs to be even lower. A study reviewing the Grand Bargain commitments (that were made in 2016) found the share of funding going directly to domestically registered NGOs to be at 5%. The Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2020 found that direct funding dropped from 3.5% in 2018 to just 2.1% of total humanitarian assistance in 2019.

Each source tells the same story. There has been too little progress, too slowly.

Why We Should Change: Self-determination and better outcomes

Like many in the community, we believe that continued effort toward localizing development is critical. But we wanted to reflect and truly consider why this is important, so we could more easily identify what success would look like. We acknowledge that different donors come with different motivations and priorities. For our own purposes, we focused on two major themes:

- Self-determination is a fundamental human right, and any work should arc toward advancing this priority. Our colleagues at the HPG literature review described the status quo this way, “the persistence of an unjust distribution of power…often kept those most affected by crisis furthest away from decision-making about how to respond to them.”

- Localized development (whenever appropriate) is more economically efficient and leads to better outcomes. In addition, while the evidence base on secondary benefits is not yet adequately developed, there are indicators that point toward clear potential additive impact from localizing development, including growth of local economies surrounding development activities, upskilling of individuals engaged in programs, and empowering citizens which can lead to more effective and accountable communities and governments.

Joining the Broader Conversation

We kick-off our exploration of these issues with a few critical and transparent disclosures. We know this area is fraught with potential disagreements, and misinterpretation of earnest dialogue is all too likely. To that end, we approach this topic with humility and a desire to learn and contribute in the way GDI knows best: exploring practical, systems change solutions; recognizing all good ideas become great solutions through a process of learning, evolving, openly considering advice and criticism; and valuing flexibility over rigidity.

We would like to specifically note that the language surrounding this area is particularly challenging. In this article, we explore our initial thinking on how to respectfully dialogue on these issues, and more about how we’re defining these issues in our series. We invite you to consider our initial exploration into the language as you join us in this learning journey.

Where We’re Starting: Funding flows

While funding flows are a primary indicator, they are only one of many areas where localizing work is required in the development and humanitarian sectors. Funding for social impact businesses is similarly lopsided in favor of founders in the global north. Representation of impacted communities remains low within organizations setting development priorities. “Knowledge creation” and ownership is concentrated in the global north, targeted at global north audiences, and offers little shared back with the communities they “analyze”. Even basic working norms within “headquarter – field office” structures, requiring local nationals to conform to time zones and working norms in the global north, perpetuate colonial ways of working.

So where should we start? In development, like in other industries, money is a proxy for power, so a concerted push to change funding flows is a logical first step. Funding domestic organizations directly can be an effective catalyst to transfer ownership and decision-making power to communities where development takes place. It also provides a tangible, measurable metric to hold organizations accountable.

We are starting our efforts by focusing on funding flows to non-profits and civil society organizations. We selected this channel for a few reasons:

- The non-profit channels often have the closest proximity and direct control over service delivery to communities. Localizing decision-making within this channel, we believe, is a difficult but relatively direct route to empowering communities being served, in the short-term.

- In the long-term, strengthening domestic civil society ecosystems strengthens (or creates) a mechanism to hold governments accountable and put pressure on them to be more transparent, efficient, and people-centric.

- This approach leverages our own comparative advantage of deep experience with and therefore ability to influence the non-profit ecosystem that includes funders, NGO recipients and intermediaries.

While it is outside our approach, we support and applaud our colleagues who are considering other pathways to progress, including increasing funding to LMIC governments, catalyzing domestic philanthropy, and private sector investment.

Over the past decade there have been multiple, public commitments from global north funders and organizations to change existing patterns. In 2010, USAID launched its Forward program that committed to providing 30% of program funds directly to local entities by 2015. The Grand Bargain of 2016, built on years of advocacy to “decolonize” the humanitarian sector, included a commitment to ensure that at least 25% of funding goes to local organizations. Ambitious targets continue to be identified, with USAID committing to 25% of funding going directly to local partners in the next four years, and 50% of programing will “place local communities in the lead to either co-design a project, set priorities, drive implementation, or evaluate the impact of our programs.” While these commitments demonstrate a will to localize development funding, they seem to have barely moved the needle on actual funding flows. Why?

Overcoming Obstacles: Identify practical solutions and scale systemic change

We believe there are two significant issues at play, which we plan to explore further in subsequent articles in this series:

- There has been too little focus on understanding and practically addressing concrete structural barriers at scale. The motivations and incentive structures of many global north funders are not built to support localization efforts. The “risk” tolerance, time and resources needed to find, due diligence, and invest in new, domestic organizations far exceeds the incentives to do so. Capacity building is required, but current pathways aren’t making adequately scaled impact. Individuals within donors and intermediary organizations are rewarded for their ability to cleanly manage projects, not necessarily to change systemic dynamics. Meaningful progress requires real, practical solutions to address these barriers.

- Change, particularly systemic change, is hard. In this case, it requires changes across a range of actors (donors, recipients, intermediaries) with diverse motivations and abilities to act. Few organizations have the ability to influence this entire spectrum. This systemic change is made even more challenging because the issue is entrenched, and needs transformation at significant scale.

In some ways, the decolonizing and localizing development “space” is already very crowded, so when we approached this issue, we asked ourselves what unique contributions we could make, and how we could learn from the good work already being done. Part of our exploration has been internal – how do we set up our own structures, systems and processes in a way that is just and equitable? Part of this exploration is external – what concretely is holding back the sectors from localizing? Where are we well suited to support progress? How do we, together with others, launch those activities and set them up for long-term success?

We’re starting this process by sharing initial perspectives for feedback and discussion through a series of articles. We don’t have all the answers but we are interested in problem solving with the community, and, consistent with our values, turning good ideas into action together.

Our Proposed Goal: Majority of funding flows directly to domestically registered NGOs

As part of our exploration process, we want to propose an ambitious end goal. We want to support flipping the script on development, advancing solutions that eventually will result in the majority of funding going directly to domestically registered NGOs. Any progress is good, but significant movement will be transformational.

Our goal is for the majority of funding to flow directly to domestically registered NGOs. This goal has the potential to unlock other localizing development priorities including building and supporting a vibrant local development ecosystem with local donors and intermediaries; driving models of participatory and collaborative development; and empowering people everywhere to lead the development of their communities.

We recognize there is no one-size-fits-all solution. There are legitimate questions to be asked and discussions to be had on key questions where there isn’t uniform agreement in perspective. Those questions range the gamut, from how do you define a domestically registered NGO, to whether all development should be localized, to whether it is even appropriate to make incremental progress, to whether effort should be focused on making the current system better, or whether it is better to dismantle the current system and rebuild from scratch.

Next Steps

We’ll be sharing our perspectives on these issues along the way, recognizing these initial points of view may evolve, grow, and become more sophisticated as we learn and continue our work in this process.

Thank you for joining us in our journey to support the decolonizing and localizing development community. At GDI we are committed to supporting this work by identifying specific, tangible solutions to address barriers and determining what we can do to concretely advance those solutions. These efforts include transparently considering and proactively working to localize our own approaches and ways of working. Later in this series we’ll be sharing more about our internal and external work in this area, and we invite feedback or questions.

We look forward to partnering with you as we move ahead.

Join our mailing list for updates and follow this series for our latest thinking on GDI’s work in this area.

*Note on methodology: When calculating the share of bilateral ODA going to domestic NGOs from OECD data, we take the numerator as “Bilateral ODA going to developing country CSOs” / “Bilateral ODA going to CSOs for the year 2019 for DAC members and other official providers”. The numerator includes both ODA going “to” and “through” “developing country CSOs”. In the denominator, we do not include bilateral ODA routed through other channels aside from CSOs, such as recipient governments, private sector organizations, public-private partnerships, multilateral organizations and regional development banks.

Similarly, for philanthropic funding, we look at the share of funding going to “developing country CSOs” / Total funding going to CSOs. The aggregated view compiled by GDI is based on OECD data available for 27 private funders.