Localizing Development: Proposed Supply Solutions to Overcome Barriers

This post is part of a series of articles where we will explore the landscape, challenges, and potential solutions to support localizing development. We will also be exploring bright spots, and creative ways our colleagues are moving development and international relief closer to the communities they impact.

This article and series were developed through consultative conversations with our global team at GDI and cross-sector experts representing diverse perspectives around the world. We reviewed more than 50 articles and opinion pieces, and over 20 long-form reports. We spoke with 25 individuals at non-profits, networks, foundations, activist organizations, and social businesses, all of whom engage deeply with this topic in their work. We are deeply grateful for their time and insights.

For more context on the language we use in this series, please review this article.

In our last article we explored potential solutions to address barriers for domestically registered organizations to receive international funding. In addition to those solutions, we believe new, practical pathways are required to address challenges donors face providing funding to domestically registered organizations. Without considering and addressing constraints on both sides, we will continue to see limited progress. As with our previous article, we’ll be considering solutions that consider different segments of the market as we look to identify feasible and targeted solutions.

While we’ll present and consider these solutions individually, as we noted in previous articles, some of them will be most effective when launched in concert with complementary solutions.

Proposed Solution 1: Catalog Domestically Registered Organizations

ALL ORGANIZATIONS

One near constant refrain we heard during our research and interviews was that donors simply aren’t adequately familiar with the ecosystems of domestically registered organizations in a country. There was near uniform belief that a simple catalog of domestically registered organizations could be transformational.

But our conversations also highlighted that several of these cataloging efforts exist, targeting slightly different parts of the market. Global Giving, Building Markets, Adeso, Ashoka, NGO Source, Catalyst 2030, and Echoing Green were just a few of the organizations that our colleagues mentioned as attempting to address this issue. USAID recently launched its own platform to identify more domestically registered organizations, and several aid transparency platforms such as IATI and FSRS offer additional pathways to identify potential partners. Further, many country governments provide lists of registered NGOs.

We approached our exploration with a hypothesis that the community needed a new platform to catalog domestically registered organizations. We no longer believe that is necessary. Instead, we believe these cataloging efforts would benefit from defragmentation, with an investment in bringing best practice, learning, and data together to maximize impact. These many data collection threads would be stronger woven together. Ideally this disbursed data could begin to be centralized into one platform, but even an intentional landscape effort to “catalog the catalogs” could be additive.

We further believe there would be good value in developing a Multi-Stakeholder Initiative (MSI) consisting of engaged data consumers (donors), data collectors (current platform “owners”) and data providers (individual NGOs) to curate best practice, refine a standardized baseline in data collection, and ensure coordination over time. In addition, this MSI could identify new ways to centralize due diligence data collection, or create new certifications for NGOs that meet certain operational standards. This initial vetting could further expedite donor’s ability to identify and engage domestically registered organizations, replacing duplicative, tedious, and time consuming background assessments. The STEP effort by Tech Soup’s Global Validation Services aims to address some of these priorities by creating a tiered due diligence framework with local evaluations.

Proposed Solution 2: Create Fiscal Intermediaries

Fiscal intermediaries have an important role to play in localizing funding through managing risks and breaking down transaction sizes. We believe fiscal intermediaries specifically designed to address this need can have a significant impact on localizing development. New fiscal intermediaries should be registered in the global south, maintaining strong relationships with, and accountability to, the communities they serve. Staff, leadership, and boards should represent those receiving funding, and be tirelessly committed to finding and supporting opportunities to shift power, funding, and decision making authority directly to impacted communities.

Different types of domestically registered organizations, and different award sizes require different types of intermediation. While facilitation of funding might be centralized in one organization, we would envision unique organizations designed to specifically address the unique needs of differentiated segments.

MICRO AND SMALLEST ORGANIZATIONS

Achieving stated donor goals to localize international funding will likely require significant growth in the number of small, medium, and large sized domestically registered NGOs capable of absorbing this funding. While brand new organizations may be part of resolving this barrier, the growth of existing domestically registered organizations to take on additional funding, expanding in scope and scale, will also be necessary. We fully acknowledge that some micro-NGOs (annual budgets under $100,000) may either prefer to operate on a smaller scale, or are best able to serve their communities by constraining their own growth. However, other micro-NGOs could leverage initial funding to expand, building the cadre of organizations suited for larger scale international funding.

The characteristics of micro-NGOs make scaled international funding particularly difficult. Award sizes generally need to be very small. And while it is impractical to build robust compliance infrastructures, it is equally necessary because micro-NGOs are often perceived as creating the most significant donor risks.

We recommend the creation of intermediaries that can create portfolios of micro and small NGOs to receive pooled, outcome focused funding. These portfolios of organizations would be mutually accountable for outcomes, de-risking activities for donors while creating synergies and promoting learning and knowledge sharing to build capacity of organizations in the portfolio. There are some promising examples of intermediaries focused on supporting coalitions of community based organizations. One example is the Local Coalition Accelerator, which supports the design and execution of cross-sector community development plans, and helps to build bridges for future direct investment in local groups by bilateral donors. We see an opportunity for these intermediaries to demonstrate a pathway to include unrestricted and restricted projects.

SMALL, MEDIUM, AND LARGE ORGANIZATIONS

During the interview process we were surprised by how consistently we heard donors lamenting the dearth of domestically registered intermediaries to facilitate funding of small and medium sized awards to domestically registered NGOs. We entered our conversations assuming global north donors would prefer to provide funding directly to small and mid-sized international organizations (annual budgets from $100,000 to $5 million), with IRS regulations serving as the primary barrier to funding domestically registered organizations. However, we discovered that most donors believe their internal policies and systems were not well suited to supporting and providing appropriate risk-responsive monitoring of smaller international NGOs. We believe this space could be filled with new domestically registered intermediaries focused on providing these services.

MEDIUM AND LARGE ORGANIZATIONS

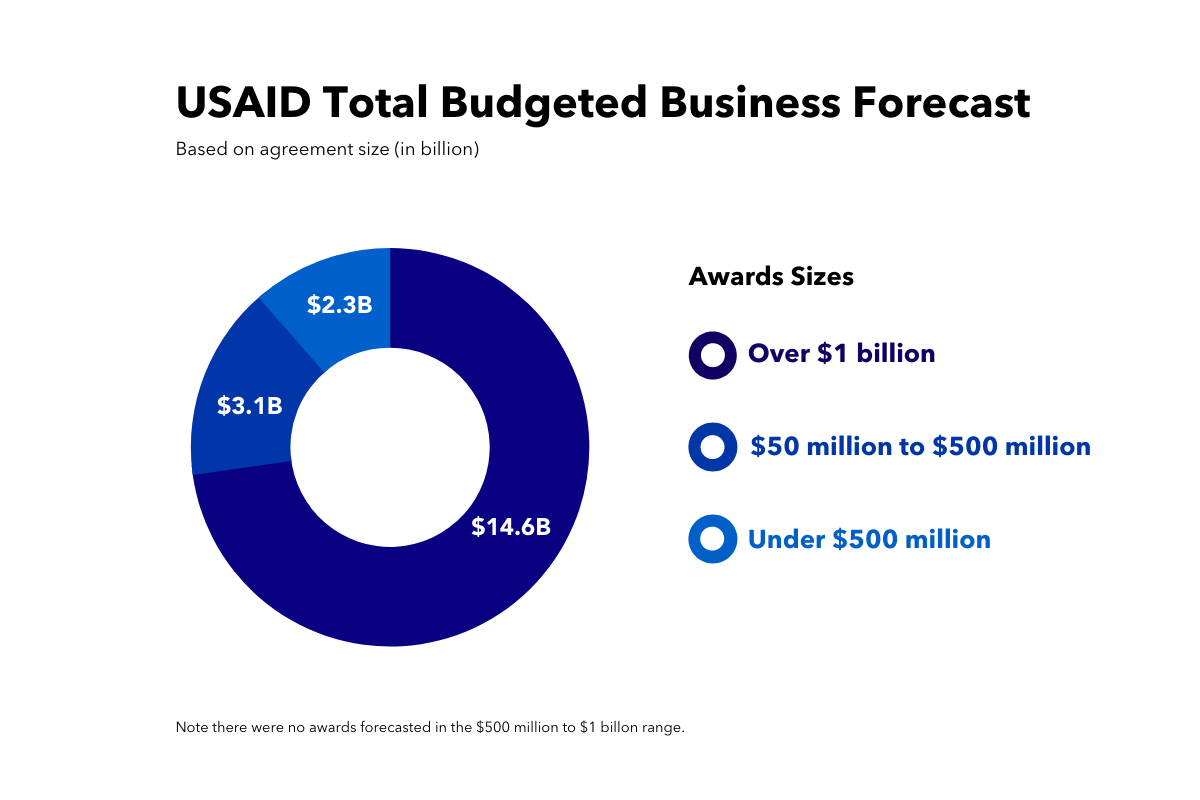

One of the most significant barriers to funding localization targets is the mis-match between award sizes made by major bilateral donors and domestically registered organization’s ability to absorb awards of those sizes. USAID’s December 2021 business forecast includes five projected awards valued at over $1B each. Assuming those very large awards are unlikely to be awarded to domestically registered organizations, the overwhelming majority of all remaining prospective funding would need to be awarded to domestically registered organizations to meet donor’s percentage-based localization targets.

Out of Reach: Majority of USAID funding projected to be distributed through $1B+ mechanisms

As the chart below illustrates, based on conservative award sizes, nearly three quarters of prospective USAID funding is projected to be distributed through these five very large $1B+ mechanisms. When even a much smaller $50M award feels unachievable to many domestically registered organizations, pathways to substantive shifts in bilateral funding percentages appear very narrow.

Based on USAID’s own disclosures, and what we know of international development and humanitarian relief work more broadly, many of these larger awards go to a small collection of global north based organizations that specialize in winning and administering these large and complex agreements at scale. And, bilateral donors’ preference for large transactions is likely to persist since it streamlines the donor’s award management and promotes a more coordinated approach to global challenges.

We recognize that regardless of country of registration, a fiscal intermediary that distributes and manages funding in the billions will have a significant power imbalance compared to smaller organizations and individuals in unique communities. However, there may still be space for the development of LMIC based and led corollaries to these larger global north development and humanitarian relief firms. These new organizations could offer new types of commitments to represent local populations and communities at the staff and board levels, along with a clear mandate of accountability to advance the development and capacity of domestically registered organizations.

There are several examples of domestically registered organizations that are winning and successfully managing larger USAID awards, but they tend to be more narrowly focused on a single country, or a single priority. Leveraging the built in skills and capacities of these organizations, either through a joint venture or other mechanism, could be a good starting place to consider LMIC growth in organizations to manage high dollar value bilateral funding.

Proposed Solution 3: Develop New Donor Accountability Mechanisms

ALL ORGANIZATIONS

Organizational change is hard. And it is particularly difficult in government agencies and foundations. Public oversight and public scrutiny, particularly around widespread, but often baseless concerns around fraud and mismanagement, creates risk aversion. Organizational goals don’t always align with individual incentives, and the risk of a project not going well matters more than achieving potentially greater impact, especially over time, in funding domestically registered organizations. There’s also a layer of incumbent intermediaries that benefit from the risk aversion.

So, how do you help shift these donor organizations and the broader system? We see three potential ways.

First, the hard work of reviewing procurement policies, procedures, and processes needs to be done to identify areas that may limit a donor’s ability to solicit from, and provide funding to, domestically registered organizations. Organizational goals, as well as individual incentives and performance plans, need to be adjusted. Significant training needs to be conducted to meet new requirements and build new capabilities. Operational funding needs to shift, potentially toward locating program and grant managers closer to the organizations being funded and communities being served. Omidyar Network India (an impact investor that does both for-profit investments and grants) has gone a step further by creating a local geo-entity with its own strategy, with an empowered country leadership and entirely local staff that drives funding decisions. Over time, with strong leadership and support, these operational shifts will lead to a new organizational culture and set of norms. We see independent organizations, such as the Center for Global Development, as well-positioned to help provide the intellectual leadership here, particularly with government agencies.

Second, we need to build the evidence base of the efficacy and value of localizing development. Initial research from ODI shows that the risks of localization are based more on perception than empirical evidence. While ODI’s report comprehensively considers the information currently available, this work and evidence needs to be expanded to create a broad consensus that localizing funding is a better use of resources. It needs to be robust enough to address concerns from public oversight bodies, provide cover for government agencies, and build an evidence based foundation to prioritize the internal changes noted above. Moreover, operational research can help inform the best ways to localize development, maximizing efficiency and outcomes.

Third, and finally, we recognize that organizational change of non-commercial entities may be unlikely without some external pressure, or at a minimum, transparency. An objective rating system for bi-lateral government agencies, and for foundations, that collects quantitative information (e.g., funding flows directly to domestically registered organizations) and qualitative information (e.g., grantee feedback on power dynamics, decision-making and flexibility) may create a race to improve. A similar system for the large development contractors and iNGOs may also ensure authentic commitments to localizing development and even help inform award decisions by donors to support their own internal goals. Other rating systems – such as the World Bank Doing Business Report – have helped improve business conditions in countries as government agencies work to improve their scores.

Where Do We Go From Here?

As we begin to wrap up our initial exploration of barriers and practical solutions to localizing development funding, we consider where we go from here. At GDI, we’re approaching this with several priorities:

- We look for feedback, critique, and refinement of the recommendations we’ve put forward to strengthen these proposals. Please reach out to us to share your own perspectives: localizingdevelopment@globaldevincubator.org

- We will be exploring ways to make these recommendations into living solutions, considering donors and other partners that want to invest in progress using one or more of these approaches.

- We will be sharing more about GDI’s own journey to consider how we need to localize and decolonize our own work. Similar to other advantaged global north organizations, we need to be transparent about our work, and how we are, and are not, advancing these ideals. We’ll be sharing more about this journey in our next article in this series.

- And finally we want to continue to explore other opportunities and practical models for progress. We’ll do that through highlighting unique and innovative approaches that might inspire a wider audience and expanding our consideration of how to localize or decolonize in areas outside of funding flows.

We invite our colleagues to join us in this process, considering actionable ways to make real progress both in their own organizations, and through new approaches in the community at large. We invite you to share those thoughts with us so we can highlight them and continue to encourage each other in our work.

Join our mailing list for updates and follow this series for our latest thinking on GDI’s work in this area.