Localizing Development: Proposed Demand Solutions to Overcome Barriers

This post is part of a series of articles where we will explore the landscape, challenges, and potential solutions to support localizing development. We will also be exploring bright spots, and creative ways our colleagues are moving development and international relief closer to the communities they impact.

This article and series were developed through consultative conversations with our global team at GDI and cross-sector experts representing diverse perspectives around the world. We reviewed more than 50 articles and opinion pieces, and over 20 long-form reports. We spoke with 25 individuals at non-profits, networks, foundations, activist organizations, and social businesses, all of whom engage deeply with this topic in their work. We are deeply grateful for their time and insights.

For more context on the language we use in this series, please review this article.

Our initial exploration into localizing development was based on an idea: there are barriers to progress that need practical solutions if we want to make significant progress. We explored those barriers in detail in our previous article. As a consensus came together outlining the issues, it was time to identify practical solutions.

As we considered solutions, a recurring theme arose: how could we most efficiently address capacity gaps at scale? There is a significant chasm between donor commitments to directly fund domestically registered organizations and where we are today; to effectively address this we knew we needed to consider solutions that had the potential for significant scaling. What that looked like might vary: for one solution it might include leveraging scalable technology, for another it might include catalyzing a larger commercial market to serve a need, and for another it would look like demonstrating proof of concept in a pilot phase that could be easily replicated.

Before we begin exploring potential solutions, it is critical to acknowledge that many passionate individuals and organizations are already working to localize or decolonize development. We’re familiar with many of these organizations, and are inspired by their creativity and breadth of approaches to spur real progress. We hope to highlight some of these organizations and ideas later in this series and welcome recommendations on innovative approaches that we should consider learning about and sharing.

How We Evaluated Potential Solutions

In addition to scalability, we saw another key challenge: solutions addressing individual barriers might make incremental progress, but the launch of multiple solutions in tandem promised the most significant impact. We needed to consider which were absolutely required to move first, setting the stage for success down the road. We began looking at factors such as:

- Whether there is any current mechanism serving that need, even if subscale or suboptimally

- Whether the solution’s success is heavily contingent on another solution moving forward first, or in parallel

- How time consuming or complex the solution is to launch or prove the concept

- Where we have the strongest resonance in interviews with potential stakeholders

- What solutions GDI individually could have the most influence over because the solution is not contingent on current actors outside of GDI changing their internal processes or approach.

Categorizing Market Segments

Throughout our process we grouped solutions by two characteristic sets: (1) did they solve a barrier for donors, or for funding recipients and (2) what size domestically registered organization were they most likely to impact.

In this article we will consider solutions to support funding recipients, which we consider the demand side of the equation. These proposals will consider how to expand the capacity of domestically registered organizations to receive funding. In our next article we will consider solutions to support donors, or the supply side of the equation. It will explore options to expand capacity and options to give funding to domestically registered organizations. Throughout both articles we’ll consider solutions to impact organizations of a variety of sizes, recognizing their needs and challenges can vary significantly. In this series we’ll use the following terms to describe domestically registered organization based on annual budget size:

- Large: Greater than $5,000,000

- Medium: $750,000-$5,000,000

- Small: $100,000-$750,000

- Micro: Less than $100,000 (informally this segment if sometimes referred to as “grassroots”)

We recognize this distribution is imperfect at best, and the characteristics of organizations within these bands can vary greatly. But in general, we believe that these dollar figures represent tipping points where the needs or organizations, and challenges they face, begin to transition.

Demand Side Problems: Managing Donor Requirements and Scaling Domestically Registered Organizations

THE PROBLEMS: Subscale operational infrastructure and subscale cadre of operations professionals for NGOs

- Small and medium sized domestically registered NGOs are not able to provide donors with adequate confidence that they can meet compliance and management requirements.

- There aren’t enough domestically registered organizations at scale to effectively receive significant funds from global north donors.

- Limited numbers of in-country, highly qualified operations staff limits domestically registered organization’s options to develop and demonstrate operational excellence.

A quick skim of the characteristics of domestically registered organizations consistently showed much smaller scale organizations, dwarfed by their global north counterparts, and significantly smaller than the country registered affiliates of international organizations. As discussed in our previous article outlining challenges, it remains difficult for these smaller, domestically registered organizations to secure significant funding from global north donors, particularly considering a minimum organization size was generally required to fund the type of infrastructure donors were coming to expect.

USAID administrator Samantha Powers described the challenge this way:

Often, there’s just a lot of gravity pulling us toward very large, often U.S.-based contracting partners that may deign to enlist local partners as part of the overall contract or grant. But fundamentally, the investments are not made in that internal capacity and that ability to have the accounting capacity, the ability to comply with USAID regulations, which many of which are in place in order to be responsive to the need for oversight that you [the congress] have.

Administrator Power’s comments highlight a critical point that is confirmed by OECD data highlighted in their 2020 report, “Development Assistance Committee Members and Civil Society”

Donors believe domestically registered organizations offer compelling programmatic strengths and benefits, while concerns about direct funding largely center around operational barriers.

Where Do We Start?

Here perspectives on the path forward begin to diverge. We can either look for donor requirements to change OR we can build a system to meet the needs and expectations of donors. For our approach we are starting with strengthening recipient capabilities to meet current donor requirements rather than focusing on changing donor requirements. While we appreciate the value of donors streamlining their expectations, efforts in this area have had limited impact to date. In the context of our recommendations, adjusting donor policies and behavior do not meet our criteria for scalability, efficiency, and ability and likelihood of outside parties to substantially influence.

Current donor compliance requirements necessitate highly skilled staff in a range of areas, from operations, to finance and accounting, to monitoring and evaluation, along with robust governance and IT infrastructures, along with strong policies and procedures in areas ranging from contract monitoring to safeguarding.

While donor requirements for this type of infrastructure raises the operating bar of organizations, funding for these investments most often must come from the donor’s indirect cost allowance or unrestricted funding. With indirect cost caps at many donors ranging from 7% to 20% for many bilateral and private donors respectively, significant organizational scale is required to build an indirect cost base large enough to create the necessary indirect infrastructure. Ironically, those donors with significantly more rigorous compliance infrastructures tend to also have much lower indirect cost rates allowances, further exacerbating the challenges.

Illustratively, an organization with a $1M budget may only receive $100,000 (10%) from donors to cover indirect costs and investments. One highly skilled finance and compliance officer may have total compensation and benefits of $70,000*, leaving only $30,000 for the rest of the organization’s overall management, indirect costs, policy development, staff development, systems, and infrastructure. For most organizations, this math simply does not work.

Case Study: Funding Flows in Kenya

This challenge quickly becomes a chicken and egg issue, the organization needs funding to scale to a size to build donor expected infrastructure, but has difficulty securing those funds because they haven’t fully built out this infrastructure.

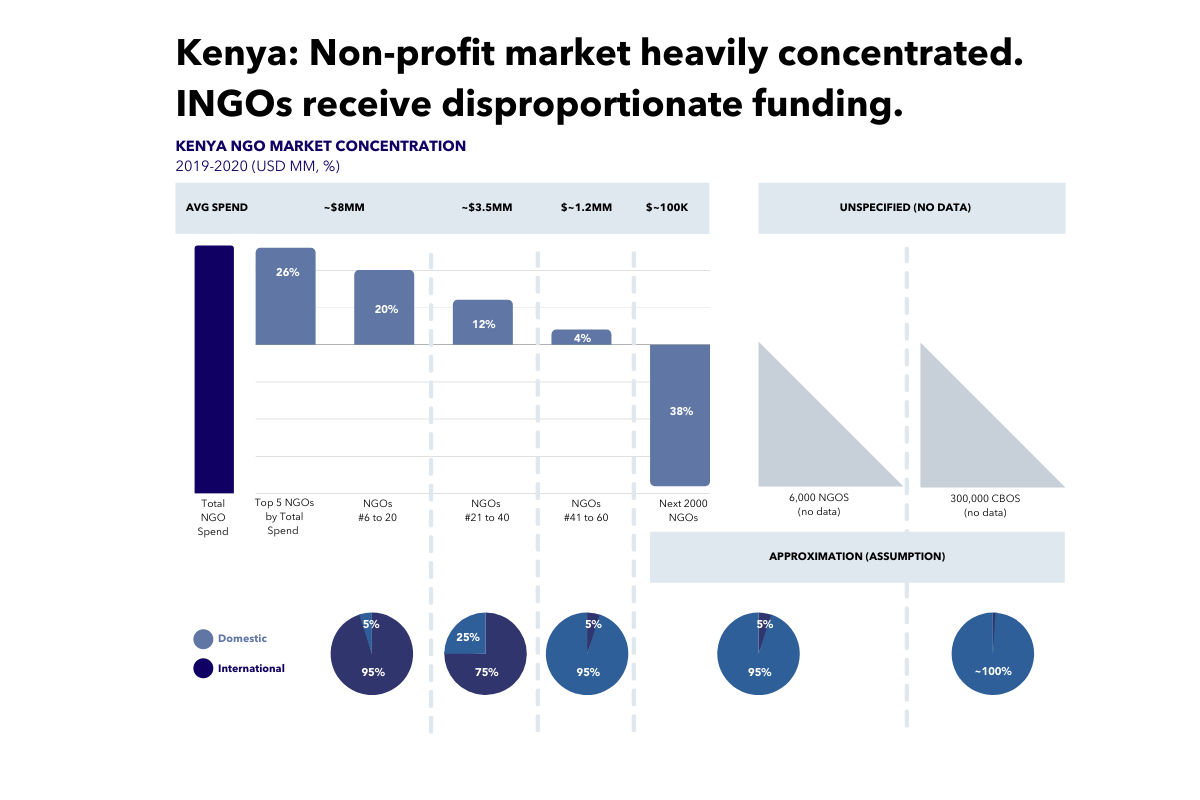

Kenya NGO board data illustrates what this challenge looks like in Kenya. In Kenya, only 54 NGOs report annual budgets over $1M. 65% of those 54 organizations are affiliates of large international NGOs. From here, budget sizes continue to go down, we assume much smaller average budget sizes of approximately $100,000 for the next 3,000 NGOs that do report data with an additional 6,000 reporting no data at all.

This data highlights two major challenges to increasing funding to domestically registered organizations.

- There are very few organizations that are at a size where it is affordable to build the in-house financial, compliance, and operations infrastructure major global north and bilateral donors have come to expect.

- The small collection of organizations that are large enough to build this infrastructure are predominately “affiliates” of larger US organizations. In addition to having more funds to work with, they often can benefit from the highly specialized expertise of their US counterpart, and may receive significant infrastructure, policies and procedures, and systems at no or very low costs. This disparity further widens the gap.

Proposed Solution 1: Shared Services Platform

SMALL AND MEDIUM ORGANIZATIONS

We propose that a shared services model that allows domestically registered organizations to share the cost to build and maintain operational staff and infrastructure could be the key to unlocking this barrier. A shared service provider would offer the necessary compensation and job stability to attract the limited pool of expert country resident staff, allowing smaller domestically registered organizations to purchase a “share” of the time of these highly qualified staff, gaining the advantage of the same expertise that previously had been largely constrained to international NGOs.

We expect NGOs with budgets as small as $100,000 and as large as $4M could benefit from this type of platform, although we expect that at $2M many organizations could begin to transition to bringing these activities in-house. Shared service platforms should be explicitly designed to support the growth phase of these NGOs, with an intentional goal to build their own internal capacity and to help organizations reach the scale required to bring these activities in-house over time.

We frequently see this model in the United States, across a broad range of organizational functions. We often fill this function at GDI during the incubation process, allowing new organizations to leverage our internal Finance & Operations, Brand, Marketing & Communications, and Talent teams. With a similar approach, new organizations could gain access to highly skilled talent at a fraction of the cost, strategically meeting their evolving needs until they have grown to scale and can bring these functions in-house. We often refer those incubated initiatives to other shared service platforms as they conclude their incubation process: co-employment organizations (PEOs); client services firms specializing in accounting, recruiting, and IT; consultants and law firms specializing in donor compliance, and organizations specializing in M&E. If this shared service model is so well developed and normalized in the US, why hasn’t this market developed more fully across LMIC domestic markets?

We believe this is another chicken and egg issue, and it needs an intentional effort to break the cycle. This services market has too little demand because the domestic NGO sector is not at a scale to create this demand; and, the NGO sector can’t grow to create this demand until the services market is more well established and donor funding increases. We’ll be looking for one or more donors to partner with us in our vision of piloting the building of a shared services market, with the intention of catalyzing transformational impact in the funding going directly to domestically registered organizations

In a future article we look forward to sharing more about what this shared services model might look like, and how we believe it can be scaled to support transformational global impact.

Proposed Solution 2: Upskilling and Developing Organizational Capacity through Technical Assistance

ALL ORGANIZATIONS

Many donors invest in varying types of capacity building for their awardees, from requiring prime contractors on large awards to conduct capacity building as part of their work, to deploying technical assistance directly. It is relatively well accepted in the international development community that capacity building plays an important role in strengthening the domestic ecosystem. But even with these investments in capacity building, overall progress to strengthen the ecosystem of LMIC domestically registered organizations remains slow.

We believe this can be attributed to several factors:

- Capacity building is targeted to a very small segment of the domestically registered organization community, specifically to those few organizations that already have established relationships with donors. In order to achieve scaled growth of the number of domestically registered organizations that are able to attract and manage donor funding, technical assistance must be expanded to include those many organizations that do not currently receive funding.

- Certain areas of organizational development are much more well suited to technical assistance capacity building than others. Capacity building should be focused on areas that are incrementally less technical (for example effective hiring, meeting facilitation, and goal setting), while areas that are more technical (for example accounting, tax, compliance, and legal) may be more effectively addressed through shared services.

- Many of the organizations that are providing capacity building have a problematic incentive structure. The majority of technical assistance and capacity building is conducted by organizations that are also direct competitors to those receiving technical assistance. While we are not suggesting that these organizations are acting in bad faith, it creates an uncomfortable incentive structure that should be further considered.

- Very little current donor funded technical assistance is currently targeted toward micro organizations with budgets under $100,000/year, which make up the majority of the potential expanded partner pool. Support to these organizations would need to be highly scalable due to the sheer volume of this collection of organizations, and customized to their unique needs, prioritizing translation into local languages.

Proposed Solution 3: Online Training Platform

MICRO AND VERY SMALL ORGANIZATIONS

We recommend building a centralized online training platform that is highly customized to the needs of this segment and translated into local languages. Multiple high quality online training platforms exist (just one of many examples is Kaya, which gathers and provides humanitarian sector trainings from multiple organizations at no cost). While current platforms provide strong benefits to the international development community overall, their content is inadequately targeted to the audience, is too donor or subject area specific, is not translated, and/or the content is so expansive that it may feel difficult for a small organization to know how to effectively engage. Much of the actual training content may already exist in organizations, but needs to be brought together in a way that is highly targeted to micro organizations. Training content could include topics such as business development/proposal writing, M&E basics, project management, and program design. A more expansive version could also cover operational topics such as financial management, procurement, and governance. Content should be highly digestible and laser focused on this micro-community.

We think this could be even more impactful if the training was not only available for free, but included a small stipend for organizations that complete the training in full, incentivizing organizations to complete the full curriculum. Donors would benefit from this type of platform as it further builds out the catalog of organizations that are on donors radars, and would serve as a basic “seal of approval” of a basic skill set for organizations engaged in their communities.

Proposed Solution 4: Hub and Spoke Platform

MICRO AND SMALL ORGANIZATIONS

We also would point to other innovative models that allow for rapid and context appropriate scaling of micro and small organizations. As one example, we previously highlighted the Effective Philanthropy Multiplier (EPM) model, as piloted in China, as a highly scalable, quick to impact, context and local community sensitive model:

Instead of only driving replication one organization or model at a time, we can also invest in creating the infrastructure in a given social sector ecosystem to scale and sustain replication to the last mile. This infrastructure consists of building two “aggregators”: 1) neutral hubs located at the provincial/state, city and/or county levels that can aggregate the local organizations and needs of the local community to drive adoption of products, source locally created products, and build the capacity of local organizations to mobilize resources from local government, corporate and public donors; and 2) a nation-wide product platform that aggregates the best products (models and interventions) and facilitates their replication.

EPM has created a network of 38 hub organizations at both provincial and city levels, connecting EPM to over 13,000 local organizations. Its nationwide product platform has sourced 49 products or intervention models for different social service needs including disabilities, elderly care, child protection and environmental protection. EPM conducts roadshows together with the local hubs to facilitate the replication of these products to tens of thousands of local organizations.

This model, which actively refines based on feedback from domestically registered implementing partners shows impressive results for scaling.

In just three years, EPM has managed to achieve 49,477 distinct replications through 8,607 local community partners, including local NGOs, community groups, schools, corporates and volunteer groups. Collectively, in these three years, the replication infrastructure, together with the hard work of the brand and local organizations, has reached 65m beneficiaries and mobilized an estimated 923m RMB (130m USD) of funding.

Introduction of these types of models at a country or regional level, along with highly scalable training platforms has the potential to position the micro and small NGO community for significant scaling to meet localization goals.

We plan to highlight other innovative platforms that promote organizational upskilling and development in future parts of this series.

Proposed Solution 5: Expand Local Service Providers Capacity for Technical Assistance

MEDIUM AND LARGE ORGANIZATIONS

Medium and larger organizations often need different types of technical assistance and capacity building than the smallest organizations.

We recommend expanding and reinforcing the work of domestically registered organizations that are exclusively focused on providing TA to other domestically registered organizations. In some cases these organizations exist but are subscale, and in other locations new entrants are required. These TA providers would be sensitive to the local context and needs, and would be engaged and accountable to domestically registered organizations. These service providers would have better aligned incentives, supporting better outcomes. This mechanism could be one of the offerings of a shared services platform, or provided through other, or stand-alone entities.

Proposed Solution 6: Upskilling and Developing Cadre of Professionals in the Industry

MEDIUM AND LARGE ORGANIZATIONS

One of the stickiest issues we repeatedly noted during our investigation is a subscale cadre of highly skilled operations professionals compared to the number of individuals required to achieve adequate growth in domestically registered organizations to meet localization goals. Part of this is simply a product of a limited number of these positions currently existing due to lack of funding directly to domestically registered organizations outside of affiliates to major US entities. Building a highly skilled larger cohort will require time and intention.

In the near term, we expect that larger international NGOs that have a great deal of specialized expertise in these areas could adjust at least a segment of their business model to provide services in these highly technical areas to domestically registered organizations, at the request of and engaged by the domestically registered organization rather than as an intermediary. Significant transition of funding to domestically registered organizations should in tandem create additional bandwidth at global north NGOs which can be leveraged to good use to support the transition period.

As we continue our exploration in this area we’ll also consider whether mentorship programs, a partnership with a respected vocational school or large firm like one of the big four firms, stronger professional associations, and highly specialized longer term curriculums (to complement short term technical assistance) also could have a role to play in addressing this structural barrier.

Sharing Recommended Demand Solutions to Advance the Conversation, Build Momentum

We share these recommendations recognizing that the issue is complex, and will require a range of collaborators and interventions to make real progress. We welcome feedback from others on ways to strengthen these recommendations, or other recommendations that may address lingering demand side barriers to transitioning funding flows directly to domestically registered organizations. We also welcome feedback from those who want to join us to partner in this work, either as donors, implementers, or further expanding our network.

In our next article we’ll begin to explore potential solutions to address intermediation constraints and barriers on the supply/donor side of the funding equation. We look forward to working together to find ways to make progress.

Join our mailing list for updates and follow this series for our latest thinking on GDI’s work in this area.

*We should note that compensation rates for experienced and exceptionally skilled compliance staff tend to be uniquely high because (1) there are a limited number of individuals with these skills in country and (2) they are generally employed by large international NGO’s which are able to offer both higher salaries and more job security as they disproportionately receive higher dollar value donor funding.